Germany

Joachim Prinz was born in the tiny village of Burkhardsdorf, Upper Silesia on May 10, 1902 to its only Jewish family. His father Joseph, a man of stern demeanor and incapable of intimacy, owned the General Store. By contrast, his mother was exceptionally loving and especially close to him. In 1910 the family moved to Oppeln, the region's capital with a substantial and affluent Jewish community. Once there, his merchant father opened a mini-department store.

Four years later, his beloved mother died after giving birth to his sister. It left an indelible mark. The distant relationship with his father, coupled with an inherently rebellious spirit, resulted in breaking the emotional bond with his family and, most particularly, with its way of life. Joseph Prinz was born to a traditional Jewish family, but had become highly assimilated. Motivated by a charismatic rabbi, Prinz rejected his father's detachment by expressing an increasing interest in Judaism, a bond heightened after his mother’s death. By 1917, he had joined the Zionist Blau Weiss (Blue White) youth movement, putting him at odds with the vast majority of German Jews. To his father’s disappointment, he decided to become a rabbi.

By age 21, Joachim Prinz had earned a Ph.D. in philosophy, with a minor in Art History, at the University of Giessen. He was ordained at the Jewish Theological Seminary in Breslau where he married Lucie Horovitz, daughter of one of its most renowned professors. Already showing special gifts and a dynamism that contrasted sharply with older often pompous colleagues, he was invited to become the rabbi of the then independent Friedenstempel (Peace Synagogue) in Berlin. Only 24, he almost immediately became what the noted scholar Rabbi W. Gunther Plaut described as, “the country’s most sought-after preacher.” With powerful oratorical gifts and a new style of straight talk about Judaism and subjects of current interest, he was especially attractive to the young, but people of all ages flocked to his Sabbath services. "If you weren’t on line at 7:30 for the 9 AM service," Rabbi Plaut recalled, "you were unlikely to be admitted to an always overflowing sanctuary." But his personal life was to be challenged. The death of Lucie at the birth of their daughter in January 1931 echoed the tragic loss of his mother. It was a devastating personal blow. In May of 1932, he married Hilde Goldschmidt who became mother to little Lucie, named for his lost wife. A year later, Hilde gave birth to their son, Michael.

Urbane, sophisticated and unconventional, he broke down barriers of formality between pulpit and congregation by ice skating with his students and being personally accessible to their parents in what, increasingly became troubled times. To the consternation of many among the community’s conservative leaders, the young Dr. Prinz spoke out about the dangers of National Socialism even before Adolf Hitler took power in 1933. For a German Jewish community that dated back to the 13 Hundreds, Hitler was seen as a temporary episode, an outsider who couldn’t possibly last in their homeland. To Joachim Prinz who, despite his natural affinity for urban life, had grown up in rural Germany where it was prevalent, anti-Semitism was not something new. It was an ingrained fact of life across much of the country. Understanding that Hitler was lethal, he began early on to urge that Jews leave the country. Thousands took his advice, but many more stayed and perished in the gas chambers. Life under Hitler was a nightmare, but Prinz continued to preach his message leading to numerous arrests and constant harassment by the Gestapo.

During his eleven year rabbinate in Berlin, eventually serving the entire community and preaching in it’s largest synagogues, he founded numerous educational and cultural institutions, officiated at thousands of Bar Mitzvahs, weddings and funerals and wrote seven books including a two volume Children’s Bible and Wir Juden, warning Jews about the danger they faced in the early 1930s. In his final year in Germany he served as editor-in-chief of a Jewish periodical. He was expelled from the country in 1937 and together with his pregnant wife and two children sailed for New York.

Son Jonathan was born a month after their arrival in the United States. After the end of World War II they would adopt Hilde’s cousin, Jo Seelmann who had lost her parents and was herself imprisoned in Nazi concentration camps. Daughter Deborah was born in 1952.

The Prinz Villiage store

With Lucie

With Hilde

Berlin's largest synagogue where he often preached.

With younger brothers Kurt and Hans

Speaking at sports festival in 1934.

Prinz' Mother

The United States

In the fall of 1937, with the sponsorship of Rabbi Stephen S. Wise, Joachim Prinz began his new life by lecturing across America about what was happening in Germany. His audiences were impressed with his orator, but in a still isolationist land some rejected his message. Some conservative Jewish leaders were outraged by his “pessimism”, considering it un-American. They questioned whether this refugee rabbi shouldn't find another country in which to live. Wise reminded them that free speech was a touchstone of our democracy. Tragically, Prinz' warnings proved pto be, if anything, an understatement of what was to come.

In 1939, financially struggling and with a wife and three children to support, Joachim Prinz accepted an invitation to become rabbi of Newark New Jersey's Temple B'nai Abraham. Founded in 1853, it was one of the country's oldest synagogues. In 1924 it had moved into a monumental new building complete with school, social center, gymnasium, swimming pool and a 2,000 seat oval shaped sanctuary with a soaring hung ceiling and unobstructed views throughout. It was an ideal setting for a gifted preacher.

A magnificent home notwithstanding, the congregation was nearly bankrupt. They had moved in on the eve of the Great Depression. Donors couldn't meet their pledges and only 300 families remained. The debts were staggering and Prinz' predecessor had long since failed to provide his congregants any reason to be active or to regularly attend services. Joachim Prinz quickly brought about a dramatic change. Abraham Shapiro, whose Caruso-like voice made him one the great cantors of the 20th Century had been hired the year before and the composer Max Helfman was brought on as music director. Shapiro's powerful tenor giving voice to Helfman's original music coupled with Prinz' memorable sermons — delivered without notes — dramatically altered the tone of the services. A thousand people might attend on an ordinary Friday night. He invigorated the congregation's programs and quickly forged strong personal bonds with its members. The synagogue's dynamic was transformed, its membership soared, its financial health was restored.

with Hilde, Lucie, Micahel & Jonathan - 1939

The Newark Siynagogue

With Wise

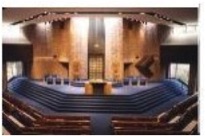

Livingston Sancturary

Once again Dr. Prinz was a force in a Jewish community. In 1945, as the war was coming to an end, he became chairman of annual United Jewish Appeal Drive. Until then, it had raised no more that $200,000 in any year. With a clear need to help Europe's displaced Jews, the goal was to bring in $1 Million. Prinz was the first and only rabbi ever to take on this task. To the astonishment of community leaders, the campaign came within a few dollars of its ambitious goal. As a result of this work, he become intimately engaged with the larger Jewish community, never again to be seen as merely the rabbi of an individual congregation.

Joachim Prinz continued to expand his role in the greater Jewish community, nationally and internationally. He held top leadership positions in the World Jewish Congress, ultimately as Chairman of its Governing Council. Having reached maturity in Europe, he had a unique understanding of post-War problems there and devoted his summers from 1946 until his retirement years, traveling abroad to address them. His first trip included a moving visit to his destroyed Berlin synagogue. He was a director of the Conference of Jewish Material Claims Against Germany. His early involvement in the Zionist movement had brought him into contact with the future founding leaders of the State of Israel, most of whom he counted among his good friends.

As a victim of Nazi discrimination, the struggle of African Americans for equality resonated especially with him. The American Jewish Congress, which he served as president from 1958-66, was at the forefront of that effort. He participated in countless demonstrations developing close relationships with his counterparts in the Black community. In 1963, he was among leaders of the March on Washington. His speech, alerting Americans to the disgrace of silence in the face of injustice, preceded that of his close colleague Martin Luther King, Jr. It was, he always felt, a highlight of his life, the culmination of all that he had stood for throughout his career.

Prinz helped his long time friend and Jewish leader Nahum Goldmann create the Conference of Presidents of American Jewish Organizations and served as one of its early Chairmen (1965-7). He wrote three more books and edited several Prayer Books. Closing in on his retirement, he helped his synagogue build and move to a new home in Livingston New Jersey. At its center was a sanctuary without stained glass windows, another radical departure from convention. Worshipers look out into the natural surroundings becoming one with, rather than separated from, the outside. This mirrored his open approach to religion, consistent with the time and needs of the next generation.

Having served Temple B'nai Abraham for 38 years, he retired from an active role in 1977, but continued to preach on the High Holidays for several more years. Together with Hilde, he spent the final years of life in their little cottage in Brookside, New Jersey -- in a sense returning to where he began, a small country village. Joachim Prinz died September 30, 1988.

In retirement at home in Brookside, NJ